Learn About Braille

Learn About Braille

Braille is a system of tactile reading and writing utilized by those who are blind (or who have very low vision). Developed in the 1820s and 1830s, the system is named after its creator, Louis Braille, a young French student who lost his vision due to an unfortunate childhood accident.

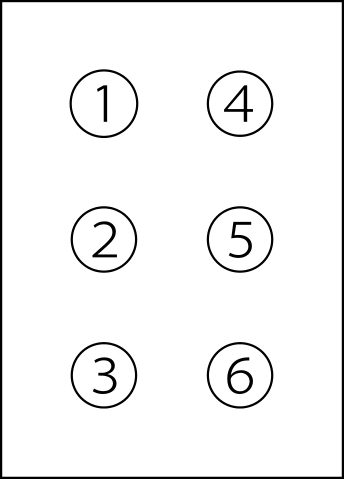

Braille characters are comprised of rectangular cells, each of which contains up to six tiny bumps or dots in a 2-wide, 3-high configuration. The number and arrangement of these dots determine what letter or symbol they represent.

Braille is not a language, per se: it is a means of representing characters in a tactile manner. In many Latin-based languages, such as English, French, or German, the basic letters of the alphabet (A-Z) are essentially the same. However, in other languages such as Japanese or Korean, the characters are designed around syllable composition. Similarly, specialized codes exist for representing non-textual information, such as musical scores, mathematics and scientific material.

Uncontracted vs Contracted Braille

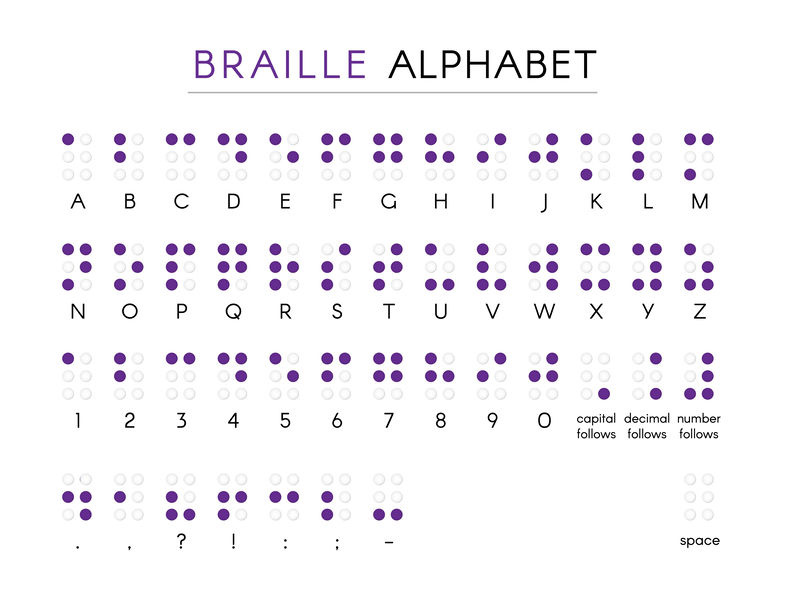

In English, the simplest form of braille is known as uncontracted or "Grade 1" braille. As shown in the alphabet below, each letter of the alphabet, and punctuation such as periods, commas, and question marks, is represented by a single character in braille.

Partly to reduce the amount of space required, and partly to speed up the process of reading and writing, the literary system of braille for English, French, and many other languages has evolved to develop an extensive array of "short forms" or "contractions" for commonly-occurring words or groups of letters. For example, the word the is often represented as a single character. Sometimes the difference can be dramatic: the word altogether would consume 10 symbols in uncontracted braille, but only 3 in contracted braille.

Reading Braille

Braille may be embossed on paper or presented using an electronic braille display connected to a computer, tablet, or smartphone.

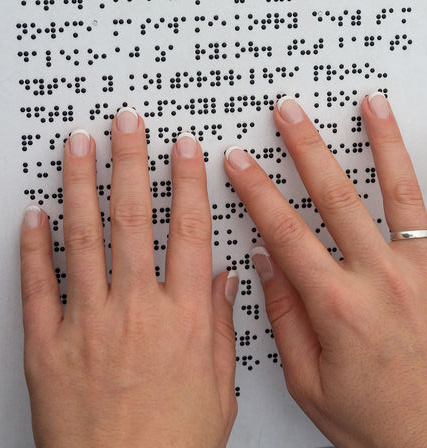

Braille is ordinarily read by smoothly and evenly sliding the fingertips (and most commonly the index finger will do most of the work) from left to right across the line of braille.

Experienced readers will use their two hands collaboratively, completing the reading of one line with the right hand while the left hand moves back to the margin to find the beginning of the next line.

Producing Braille

Braille is usually embossed onto heavier paper than you would use in your everyday life, which makes the raised dots easier to feel and helps them to retain their shape even after they have been read.

Slate and Stylus

Using a slate and stylus is the closest equivalent for the blind to "pen and paper" for the sighted. The paper is inserted between two metal or plastic sides of the slate, and a short, blunted awl-like stylus is used to punch out dots on the reverse side of the page.

Braille Writer

The Perkins braille writer is the braille equivalent of a typewriter. Using six keys (one for each dot), it can be used to quickly produce high quality braille with a minimal amount of effort.

Embossers

For larger jobs, braille embossers (connected to computers, tablets and smartphones) can quickly emboss pages upon pages of braille. Some can even print on both sides of the page (by cleverly squeezing dots for the back side in between the dots for the front).

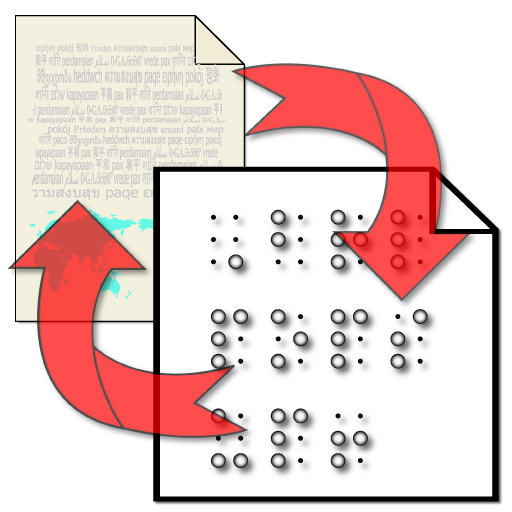

The role of braille transcribers

A braille transcriber determines how to most accurately present information from print materials into a braille version and then transcribes it into braille so that a reader who is blind obtains the same benefits from the information as his or her sighted peers.

Computer software can partially automate this process, but for all but the most routine documents, human intervention is often required. For example, how should coloured type or different font faces in print be indicated in braille? If the color is merely decorative and doesn't add information, it may be best to disregard it. On the other hand, if the colour adds information that would not otherwise be available, special markup symbols can be used to indicate colour just as they are used to indicate other forms of print emphasis.

The best braille transcribers have a keen attention to detail, strong deductive reasoning skills, good common sense and problem-solving abilities, and a willingness to continuously learn new things.

Learn more about braille

- Learn more about what braille is

- Check out the history of braille and learn how it came to be and how it has evolved

- See some fun facts about braille

- Refer to the rules and guidelines for the transcription of braille